In an interview with The New York Times, Lucasfilm has explained the reasons

behind the decision to bring back faces from the past into Rogue One: A Star Wars Story, along with the technology that made the feat possible.

A word of warning that there are spoilers ahead, so for those who have not yet watched Rogue One, you might not want to continue reading.

Making a new “Star Wars” movie can be like gaining access to a toy

collection that has been amassed over four decades. For the creators of “Rogue One,”

a film designed as a narrative lead-in to the original “Star Wars,” it

was a chance to play with characters, vehicles and locations sacred to

this series.

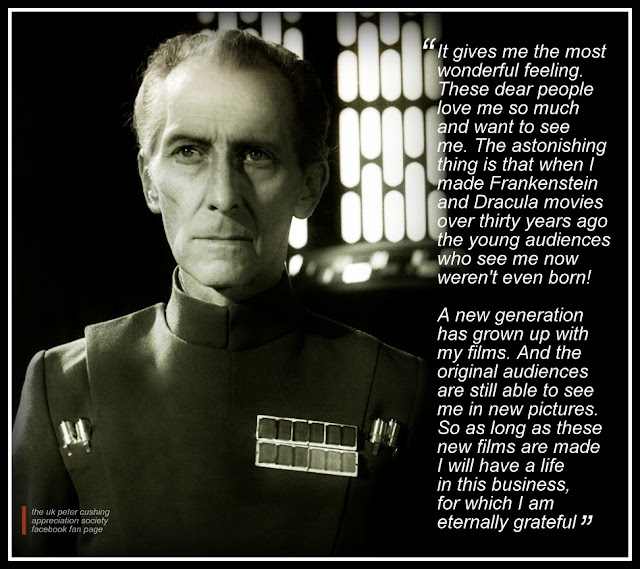

But as they revisited the 1977 George Lucas movie that started the “Star

Wars” franchise, and gave fresh screen time to some lesser-known heroes

and villains, the staffs of Lucasfilm and Industrial Light & Magic

faced artistic and technological hurdles: most prominently, using a

combination of live action and digital effects to bring back the

character Grand Moff Tarkin. This nefarious ally of Darth Vader and commander of the Death Star was played by Peter Cushing, the horror-film actor, who died in 1994.

In doing so, they also waded into a postmodern debate about the ethics

of prolonging the life span of a character and his likeness beyond that

of the actor who originated the role. The effects experts and storytellers behind “Rogue One” (which was

directed by Gareth Edwards and written by Chris Weitz and Tony Gilroy)

say they have given careful thought to these issues and were guided by

their reverence for this interstellar epic.

“A lot of us got into the industry because of ‘Star Wars,’ and we all

have this love of the original source material,” said John Knoll, the

chief creative officer at Industrial Light & Magic and a visual

effects supervisor on “Rogue One” who shares story credit on the film

with Gary Whitta. In his view, the character effects are “in the spirit

of what a lot of ‘Star Wars’ has done in the past.”

Some vintage “Rogue One” characters were easier to conjure than others. General Dodonna,

a rebel officer from the original “Star Wars” was simply recast; he was

played by Alex McCrindle in the first film and Ian McElhinney in the

new one. Tarkin presented considerably greater difficulties, but the filmmakers

said it would be just as hard to omit him from a narrative that

prominently features the fearsome Death Star — the battle station he refuses to evacuate amid the rebels’ all-out assault in “Star Wars.”

“If he’s not in the movie, we’re going to have to explain why he’s not

in the movie,” said Kiri Hart, a Lucasfilm story development executive

and “Rogue One” co-producer. “This is kind of his thing.” For principal photography, the filmmakers cast the English actor Guy Henry (“Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows”), who has a build and stature like Cushing’s and could speak in a similar manner. Throughout filming, Mr. Henry wore motion-capture materials on his head,

so that his face could be replaced with a digital re-creation of

Cushing’s piercing visage.

Mr. Knoll described the process as “a super high-tech and labor-intensive version of doing makeup.” “We’re transforming the actor’s appearance to look like another character, but just using digital technology,” he said. In striving for a balance between a digital figure who seemed real and

one who looked precisely like Cushing, the “Rogue One” creators said

seemingly minor tweaks could make significant differences — and these

details were tinkered with constantly. For example, the original “Star Wars” film (also known as “A New Hope”)

was lit differently than “Rogue One,” raising questions of how to adjust

the lighting on the character.

Hal Hickel, an Industrial Light & Magic animation supervisor, said

that lighting him “the way he was in ‘A New Hope’ improved his likeness

as Tarkin, but it worsened the sense of him being real because then he

didn’t look like any of the actors in the scene.”Side-by-side comparisons of Cushing’s daily footage from “Star Wars” and

Mr. Henry’s motion-capture performance also called attention to subtle

tics in the original actor’s delivery. As Mr. Knoll explained, “When Peter Cushing makes an ‘aah’ sound, he

doesn’t move his upper lip. He only opens his jaw about halfway, and

makes this square shape with his lower lip, that exposes his lower

teeth.” Before nuances like this were accounted for, Mr. Knoll said their

creation “looked like maybe a relative of Peter Cushing and not him

exactly.” Still, the animators had one golden rule: “Realism had to trump likeness,” Mr. Hickel said. If the overall effect had not succeeded, Mr. Knoll said there were other

narrative choices that would reduce Tarkin’s screen presence. “We did

talk about Tarkin participating in conversations via hologram, or

transferring that dialogue to other characters,” he said.

Lucasfilm and Industrial Light & Magic said their re-creation of

Cushing was done with the approval of the actor’s estate. But the

technique has drawn criticism from viewers and writers. The Huffington

Post called it “a giant breach of respect for the dead,” and The Guardian said it worked “remarkably well” but nonetheless described it as “a digital indignity.” Mr. Knoll said he and his colleagues were aware of the “slippery slope argument,” that their simulated Cushing was opening the door to more and more movies using digital reproductions of dead actors. “I don’t imagine that happening,” Mr. Knoll said. “This was done for very solid and defendable story reasons. This is a character that is very important to telling this kind of story.”He added: “It is extremely labor-intensive and expensive to do. I don’t imagine anybody engaging in this kind of thing in a casual manner"

If “Star Wars” films are still made in 50 or 100 years, Mr. Knoll said audiences would probably not see likenesses of Mark Hamill or Harrison Ford playing Luke Skywalker or Han Solo. (He noted that the actor Alden Ehrenreich had already been cast to play the young Han Solo in a coming film about that character.) “We’re not planning on doing this digital re-creation extensively from now on,” Mr. Knoll said. “It just made sense for this particular movie.”

The filmmakers also pointed to a scene at the end of “Rogue One,” when the intercepted Death Star plans are delivered to Princess Leia — who has been digitally recreated to look like Carrie Fisher in the original “Star Wars” — as an appropriate and effective use of the technology. Ms.

Fisher died on Tuesday.