In 1953, Nigel Kneale changed the face of television with his serial The Quatermass Experiment. The play, broadcast live on British television, was a huge hit with the public, establishing Kneale as a force to be reckoned with in the science fiction and fantasy genres. He would hit a nerve in 1954 with his adaptation of George Orwell's political allegory, 1984.

Around this same time, Hammer Films had optioned Kneale's first Quatermass adventure for the cinema - the resulting film, The Quatermass Xperiment (the "X" serving to emphasize the "adult" nature of the material), would become a hit for the company, thus steering them in the direction of sci-fi and horror. Following the success of The Curse of Frankenstein in 1957, Hammer continued with more Kneale adaptations, bringing their own versions of the 1955 Quatermass 2 and The Creature to the screen; the latter would be rechristened as The Abominable Snowman or The Abominable Snowman of the Himalayas, depending on the print.

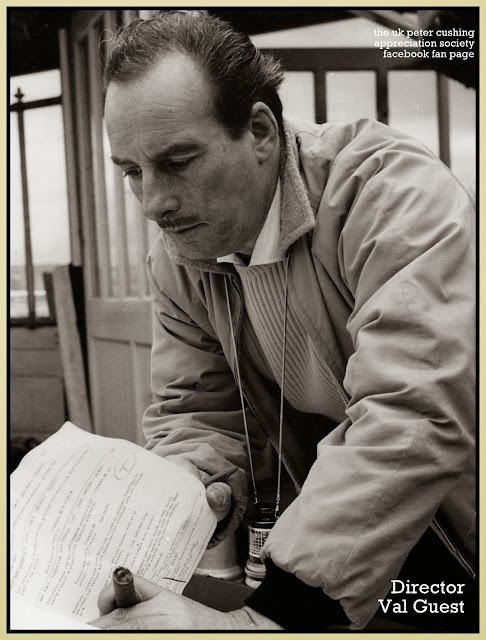

Despite Kneale's issues with his handling of The Quatermass Xperiment (and Quatermass 2, which Kneale was more closely involved in bringing to the screen), Hammer brought Val Guest in to direct. Guest broke into films quite by chance after slagging Chandu the Magician (1932) in a print interview and boasting that he could write a better film himself; the film's director took him up on the challenge and Guest took to screenwriting like a duck to water. He would begin directing unassuming programmers but would go on to direct some eclectic and very interesting pictures. He was precisely the kind of director Hammer liked: strong and authoritative on set, but capable of bringing in the film on budget without succumbing to hubris and excess. Guest would later describe The Abominable Snowman as a disappointment, citing Hammer's unwillingness to allow him to film on location, but the end product is very well crafted and continued Kneale's trend towards thoughtful, low-key sci-fi with much emphasis on characterization.

The entire cast does a fine job, notably Arnold Marle as the wizened Dalai Lama figure who seems to hold some key to the mystery of the Yeti, but the emphasis is very much on the clash between Cushing's idealist and Tucker's showman. The two actors do a magnificent job of playing off one another, with Cushing adding depth and nuance to what could have been another stock character. Cushing's fondness for improvising with props led director Guest to dub him "props Peter," while his concern over realism prompted him to question Guest as to whether or not one could actually light a cigarette at such a high altitude; Tucker's reply was along the lines of, "I don't care if you really could or not; I'm smoking anyway, so you may as well, too." Both actors thus take time to visit flavor country while stressing out over the severity of their situation.

Despite Guest's protestations of penny pinching, the film looks impressive. Arthur Grant would later become Hammer's DP of choice when Jack Asher's meticulous methods made him too expensive for the company, and his later work tended to be functional but uninspired. For whatever reason, however, he did splendid work in widescreen and black and white: thus, The Abominable Snowman joins Joseph Losey's These Are the Damned and Freddie Francis' Paranoiac as one of the best-looking films he photographed. The mood is highlighted by a spare, ominous soundtrack by Humphrey Searle, who did far too little work for Hammer. It may lack the "star value" of Hammer's better-known monster figures, but The Abominable Snowman is an unappreciated gem in their overall body of work and shows once again why Guest was the company's best director of science fiction properties.

Text: Troy Howarth

Banner and Images: Marcus Brooks