Looking to put the debacle of Madhouse behind

them, Amicus looked to another short story for inspiration. Subotsky settled on “There Shall Be No

Darkness” by James Blish. It is, in

essence, a conflation of Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None (aka, Ten

Little Indians) and Richard Connell’s The Most Dangerous Game, with elements of

the werewolf mythos stirred in for good measure.

In

the hands of first time director Paul Annett (who would later go on to direct

some good episodes of the Granada Sherlock Holmes series starring Jeremy

Brett), The Beast Must Die rattles along at a pretty good clip – but sadly, it

falls short where the werewolf itself is concerned. Sooner than make up the actor playing the

werewolf (no spoilers here, folks!), they elected to try and make a friendly

looking pooch look intimidating with some extra fur and “creepy” lighting and

camera angles. It doesn’t work. Thus, the finale doesn’t have quite the punch

that it really should.

As usual for Amicus, there’s a good cast on

display. The lead role went to

African-American Calvin Lockhart when the original choice, Robert Quarry (Count

Yorga, Vampire), proved to be unavailable; much like Vincent Price, who had

been forced to pass on The House That Dripped Blood, Quarry rankled when his

boss at American International Pictures refused to release him to do a horror

film for a “competitor” such as Amicus.

According to Annett’s commentary track on the DVD release of the film,

Lockhart proved to be difficult to deal with, as he resented that the role was

not conceived for a black actor and he believed that the producers were simply

trying to cash in on the then-popular Blaxploitation movement. In response to this, Lockhart played up the

character’s wealth and culture, resisting the urge to fall into any kind of an

ethnic stereotype. It’s an enjoyably

arch performance, but one can sense the actor struggling against the material,

and one is left regretting that Quarry was not allowed to do the picture

instead.

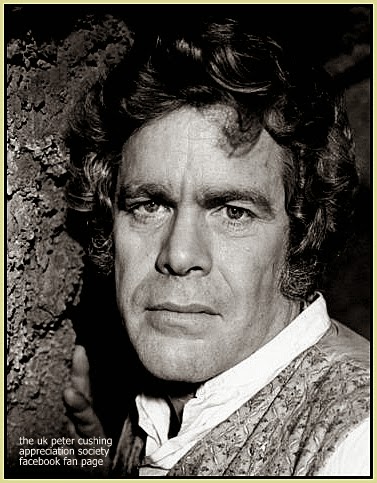

Amicus

surrounded Lockhart with some wonderfully accomplished performers, including

Charles Gray (Diamonds Are Forever), Anton Diffring (Where Eagles Dare) and, of

course, Peter Cushing. Cushing is cast

in his usual savant role, but the whodunit nature of the material ensures that

he, too, comes under suspicion of being a werewolf. Cushing doesn’t have a great deal to do here,

and he adopts a somewhat inconsistent Norwegian accent, but he’s still a

welcome presence. Diffring, often cast

as icy villains, is enjoyable in a warmer-than-usual role, as Lockhart’s

sardonic surveillance expert, while Gray is his usual acerbic and amusing self

as one of the reluctant houseguests. The

film also contains an early appearance by Michael Gambon, later to achieve fame

as the hero of Dennis Potter’s The Singing Detective and numerous films by

Stephen Frears, Tim Burton, and others. Beautiful Marlene Clark (Ganja and Hess) is the only other black actor

in the production, and she gives arguably the film’s strongest performance, as

Lockhart’s long-suffering wife.

The production looks classy enough, provided one

can accept the very 70s fashions. Jack

Hildyard (an Oscar winner for films like Bridge on the River Kwai) handles the

cinematography, which is slick if not especially memorable; some bad day for

night photography betray the haste with which the film was shot, however.

Douglas Gamley contributes a funky score which has been derided in recent years as being dated… Films inevitably reflect the period in which they were made, however, and the music is no more distracting in this sense than the bell bottoms and butterfly collars which are evident throughout. Annett handles the material with smooth efficiency, milking maximum impact from a few key suspense scenes.

Douglas Gamley contributes a funky score which has been derided in recent years as being dated… Films inevitably reflect the period in which they were made, however, and the music is no more distracting in this sense than the bell bottoms and butterfly collars which are evident throughout. Annett handles the material with smooth efficiency, milking maximum impact from a few key suspense scenes.

By

this stage in the game, it became apparent that Amicus was on the decline. Subotsky’s relationship with Rosenberg was

deteriorating rapidly and while he didn’t realize it yet, the writing was on

the wall. Even so, they plunged ahead

with an ambitious production which appealed to Subotsky’s interest in fantasy

and science fiction.

At the Earth’s Core (1976) was the second of three films that Amicus would make based on the stories of Edgar Rice Burroghs. Best remembered today for Tarzan of the Apes, Burroghs (1875-1950) wrote a number of colorful action-adventure stories, many with a strong fantasy/sci-fi component. At the Earth’s Core, first published in 1914, was the first of his “Pellucidar” series of stories. “Pellucidar” was a hollow version of the Earth, populated with various tribes and assorted creatures; in the story, David Innes and eccentric inventor Albert Perry burrow into the center of the Earth thanks to one of Perry’s inventions and encounter plenty of action and intrigue.

The success of the story lead to several followups: Pellucidar (1915), Tanar of Pellucidar (1929), Tarzan at the Earth’s Core (1929), Back to the Stone Age (1937), Land of Terror (1944), and the posthumously published Savage Pellucidar (1963), which gathered together several unpublished short stories that continued the mythology.

Taken in the spirit in which it is intended, At the Earth’s Core is innocuous fun. Director Kevin Connor does the best he can with a juvenile script and production values which, while adequate, fail to adequately come to grips with the ambitious mythology of the subject matter. The film looks professional enough, but the special effects are tacky—very much of the stuntmen in rubber suits playing monsters school—and there’s never any real sense of menace generated. Cinematographer Alan Hume does what he can to create a bit of atmosphere and Mike Vickers contributes a passable soundtrack.

The

handsome but bland McClure makes for a handsome but bland hero, while the

normally splendid Peter Cushing falls down rather badly in one of his grating

“silly old man” characterizations.

Perry, as presented by Subotsky, is an absent minded professor type and

Cushing is true to this—but it really doesn’t work very well and his constant

calling out of his sidekick’s name becomes grating. Caroline Munro looks absolutely gorgeous, of

course, as the Pellucidarian who becomes the object of McClure’s affection but

she doesn’t have much to do beyond uttering some idiotic lines and doing her

best to look threatened by the rubber monsters.

Sadly, this would prove to be the end of the line, Amicus-wise, for both Cushing and Subotsky. Subotsky would relocate to Canada for a time and gamely tried to carry on the anthology tradition with such films as The Uncanny (1977) and The Monster Club (1980); Cushing would come along for the former but passed on the latter, as did Christopher Lee—one can hardly blame them. Subotsky would secure the rights to some Stephen King properties in the 1980s and got a credit on the King anthology film Cat’s Eye (1985), but it didn’t amount to much. His final credits, again based on King properties, would be released posthumously: Lawnmower Man (1992) and Sometimes That Come Back … Again (1996). Subotsky died in 1996.

Rosenberg

would follow in 2004. The end may have

been contentious and fraught with difficulties, but the films these two men

produced together in the 1960s and 70s stand as some of the most engaging and

appealing British genre films ever made.

For Peter Cushing, they would represent some of his most interesting

character work, as well. On that level,

for sure, it proved to be a match made in heaven.

The Amicus Films of Peter Cushing was written by Troy Howarth

with images and artwork by Marcus Brooks.

Find out MORE about THE BEAST MUST DIE: